Let’s be about it: David Weber

Chances are that if you’ve spoken to me recently, or seen my Twitter feed, you’ll know I dedicated my 2019 reading list to David Weber’s Honorverse series.

You should know going in that this isn’t normal behaviour for me. I like to read as much as I can. I’m not the fastest or the most dedicated reader, but I like to mix it up, switch up my authors, the genres and styles, to make the most out of the time I put aside for reading.

So 2019 was a bit of an anomaly. And reading 10 or 11 books by the same author (and not finishing the series they’re in) is daunting at the best of times. I’ve never, not ever read another series that has so many entries, and offshoots, and side storylines, before. But here we are.

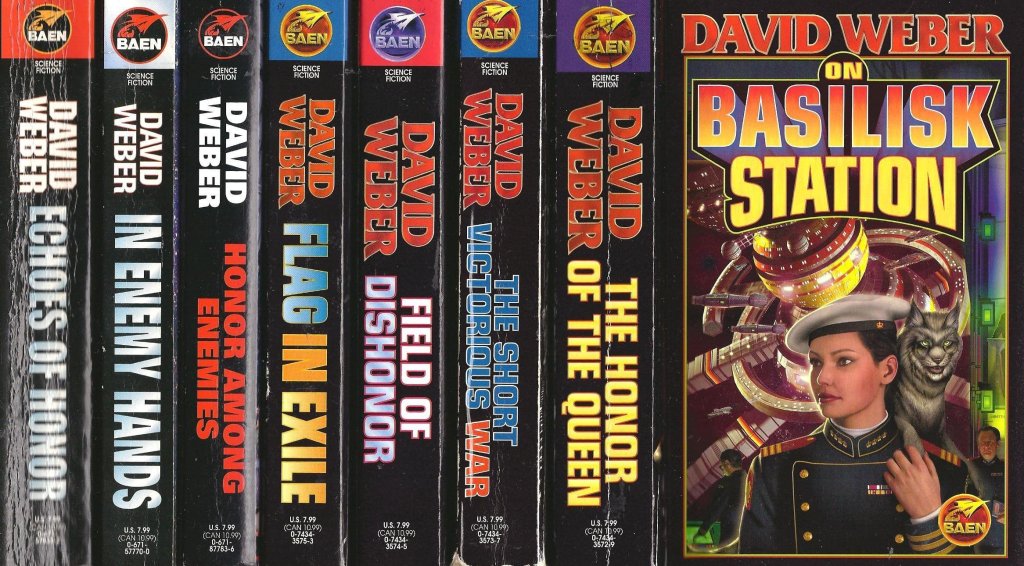

The Honorverse series starts with On Basilisk Station (published 1993), and introduces Commander Honor Harrington, and a good group of recurring characters that continue to feature throughout. This main series then goes on for another 13 novels, the most recent of which, Uncompromising Honor, was published in 2018.

I was first introduced to it by one of my lecturers, John Sayle, while I was studying Creative Writing at university. For 4 or 5 months in John’s lectures, we studied worldbuilding and the techniques speculative fiction authors use to add conflict, depth and a healthy dose of reality to their settings. In this case, Weber builds his narratives around a 2000-years-from-now, post-Earth humanity that has access to faster-than-light (FTL) travel without FTL communications, which means you often know more than the characters do about what’s happening. I think this part of his worldbuilding is best explored in The Honor of the Queen (1993), but it crops up throughout, and especially later once he begins to add point-of-view characters like Lester Tourville.

With slightly more than a subtle hint of inspiration from the French Revolution and Napoleonic-era European politics, it’s wholly unoriginal for me to say that this is Weber’s take on ‘Hornblower-in-space’. But that’s precisely what it is. And I’ll touch a little on the other implications this has for the writing a bit further in.

Why am I telling you all this?

Having dedicated 11 months to the series, I thought I’d better have something to say about it. I picked up The Honor of the Queen this time last year as a way of casually researching how Weber structured his adventures in military science-fiction.

The novel I’m currently working on, Wolf on the Fold, follows a Royal Marines captain in the midst of a cold war about to go hot. And while Alex, one of my main characters, is completely different to Honor, the truth is I’d been looking for an excuse to return to the series ever since university. It seemed like the perfect time.

It’s no doubt that fans of the series lap the books up. Of the 11 books I’ve read (On Basilisk through to At All Costs), they’ve always been rated overwhelmingly positive. In fact, to manage my curiosity, I worked out the average rating they’d scored on Amazon.

The series scores a pretty decent 4.4 out of 5 stars, on average.

In terms of ratings in the first 11 books, there are some high points: Honor Among Enemies (published 1996) scored 4.9, whereas On Basilisk Station only scored a straight 4. To be fair, I should also mention that the number of reviews goes down significantly from On Basilisk Station which has 138 reviews, whereas Honor Among Enemies only has 16 (at time of writing).

And it’s not a question of time. They were only published 3 years apart.

To me it looks like a question of stamina. Between ’93 and ’96, Weber published the first 6 books. 6 books! In 3 years. That’s a big ask of your audience, sticking with a series for 6 books is a big commitment to make. Sticking with it for the whole 14 is huge! Just 10 of those books took me a whole a year of reading.

I’ll also mention his overall rating on Goodreads is 4.13.

So, there’s clearly a demand for Weber’s writing or he wouldn’t have kept going. And the fact that other writers like S.M Stirling and Eric Flint have got in the Honorverse sandbox to play in the world speaks for itself.

In my experience, the demand comes from how easy they are to read.

There’s a few ways he does this. He’s clearly spent some time mulling over some of the concepts at the core of his work. Impeller drives, Warshawski sails and gravity waves are explained, re-explained and expanded on at almost every opportunity. For pretty casual science-fiction readers like me, he convinces you these things make sense and you trust him to carry on.

But he’s also telling a specific type of story. One that a lot of readers will be familiar with. If you don’t recognise the Hornblower-formula, then you might recognise it from Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe or James Holland’s Jack Tanner. The formulas success comes from its focus on character and how they interact with their respective world. Honor Harrington is Horatio Hornblower, she’s Richard Sharpe, she’s Jack Tanner. Now, I’m not saying that character archetypes don’t work. They clearly do.

The key difference (aside from her being a woman and living 2000 years from now) is that she has a treecat, Nimitz, a sort of semi-sentient, celery-loving alien pet pal who helps her divine people’s motives and helps feed her success. Throughout the course of the series, we see Honor take on a variety of roles, which I won’t go into here because – spoilers – but, at each turn she’s pretty much a pro unless the narrative dictates that she shouldn’t be.

She has plenty of traits that make her readable and there’s obviously some semblance of Weber trying to make her believable weaved in there too.

As a naval officer, she’s competent, fiercely brave and completely dedicated. As a leader, she’s empathetic, she engages with her crew and listens to them. She’s decisive, despite being full of self-doubt about her capabilities, her social class, the way she looks, dresses, sounds…

It’s because she’s such a recognisable and (at times) impossibly competent hero that you root for her. It’s one of the reasons you keep come back to her again and again.

I won’t labour the point much more, because I’m in danger of saying something like the formula does Weber a favour and half writes his books for him. But if you’d like to read more, as I did, then you might enjoy David Langford’s (Different Kinds of Darkness) ‘Hornblower in Space‘ column, published in Issue #104 of SFX magazine.

What I’m trying to say is that when Weber is writing according to the formula, the Honorverse is at its best. There’s a reason there are so many examples of it and it’s pretty simple – it works. It’s exciting, the narrative beats are satisfying. We get to watch our heroes get the absolute shit kicked out of them, lose what they hold dear, but ultimately emerge victorious/vengeful in the last few pages. And while you could make the argument that Weber’s 25% conclusions brush up dangerously close to being deus-ex-machinas, you don’t resent the fact that 75% of the narratives are mainly build-up at best, and filler at worst. The formula is what gets us punching the air and saying ‘Fuck yeah’ when our hero serves up their own future brand of whoop-ass. You close the book on a high. And if you’re like me, you immediately go to the Kindle store and buy the next one. This 25% is what earns Weber his average star rating. Then you’re back in the cycle. It’s addictive.

By his own admission, Weber said in a blog on TOR.com:

“…my focus is on the tale well told, rather than worrying about whether or not it’s “literature,” and that’s the way I approach my craft.”

‘All Those Details’ – David Weber, TOR.com blog, 10 July 2009

But for a minute, let’s talk about the other 75%. The build up. There obviously has to be an element of this for a story to have any kind of pay off. As a reader you need to be invested in the story, in the characters, in the situation, for it to have a satisfying conclusion. And the most heinous crime would be to waste that (I’m looking at you Benioff and Weiss).

Weber works best for me when he has more to say than the 25% at the end. And maybe because there are still gaps in my reading, that I’ve not finished the full 14 yet, that I’m missing something. But I don’t think that I am. There are a few of his books that notably stand out for me. Field of Dishonor (1994) and Honor Among Enemies (1996) are the ones I remember most clearly, though I will give a shout out to In Enemy Hands (1997) and Echoes of Honor (1998) which can only be described as a classic two-parter. The latter pair are like one of the really good Star Trek: Next Generation two-parters that you always revisit (The Best of Both Worlds, anyone?)

But Field and Enemies both do more than build-up and pay-off. They sustain the action, the drama, moving you from plot-point to plot-point naturally and building to a crescendo that makes the conclusion so intoxicatingly fulfilling.

When he’s writing at his best, you’re hungry for the next page. You know, the kind of hunger where you’re sat at your desk at work completely incapable of being productive because you’re just waiting til you can pick your book back up and dive back into the story.

Something that pulled me in with his early novels was the sense of renewal, of adventure. This is something Weber’s early installments (Basilisk, Honor of the Queen, Short Victorious and to some extent Flag in Exile) have in common. They’re the next step in Honor’s life. The new ship, the new crew, new mission or new threat, in some cases the new rank. It’s a potentially unsustainable way to write, a quick-win that offers something to new and returning readers, but it’s effective. And he does carry elements of it throughout the series by bringing back recurring characters. In this instance though, he could learn a little from Scott Lynch (Lies of Locke Lamora) or Dan Abnett (Eisenhorn). I’m never as happy as picking up a new Lynch story. The excitement and anticipation that comes with the new adventure sums up all that is great about reading speculative fiction.

It’s potentially an unfair comparison to make. The respective series for Lynch is much shorter (Gentleman Bastards, at most, will have 7 installments, with only 3 out at the moment) and Abnett’s trilogy of trilogies (Eisenhorn, Ravenor and Bequin) not much shorter that the current length of the Honorverse.

But there is definitely something that shifts between his earlier works, which were written close together, and those that followed later. As the years start to creep in between each novel, they lack the clarity and sense of direction that feels so natural early on. I get the sense that Weber wanted to develop the world past the Manticore-Haven War, which is completely justified, but my own interest started to wane with Manpower and Mesa. Each to their own.

And as for me, having gone into this wanting to learn a little about how I could apply Weber’s writing about futuristic space navy’s to my own writing, I’ve picked up a few things.

(Artwork originally by David Mattingly, 2001)

David Weber luxuriates in the glory of the Royal Manticoran Navy, the pomp and circumstance of serving Queen Elizabeth III of Manticore, the underdog narrative of the small Kingdom taking on the empire. It’s like the Honorverse is a Saturday morning with no responsibilities and he can stretch out in bed, comfortable he has nowhere to be and nothing to do, flip the pillow over to the cool side and… aaaaah.

But seriously, my main learning for my own writing will be to respect the inspiration of Royal Navy and Royal Marine tradition, and not be afraid of where my imagination takes it. If I can have as much fun and enjoy it as much as it’s clear Weber enjoys his vision of the service Honor is a part of, then I’ll be proud of whatever form it takes.

And it goes without saying that one day soon, I’ll return to the bridge of Honor’s newest starship and see where service takes her and her indomitable crew next.

The best part of this post is that you don’t even have to take my word, you can find out for yourself. I found out recently, after recommending the series to friends and family, that the first two installments, On Basilisk Station and The Honour of the Queen, are on the Kindle-store (both US and UK) right now for free.

If Amazon and Kindle aren’t your thing, you won’t miss out. Baen, Weber’s publishers, have a project called the Baen Free Library where you can also pick them up for free in a format of your choosing.

You can find out more about the Baen Free Library on their website.

Right. Let’s be about it.

Cal

- Highlight of the series (so far): Honor Among Enemies (1996)

- all the good stuff – new ship, old favourite recurring characters, new challenge, new mission, first time we see Silesia

- all the good stuff – new ship, old favourite recurring characters, new challenge, new mission, first time we see Silesia

- Lowlight of the series (so far): Ashes of Victory (2000)

- marks the culmination of my least favourite storyline and begins Weber’s exploration of things outside his comfort zone – not bad, just not my favourite

With thanks to:

TV Tropes, for helping me articulate a little of what I was trying to say

David Langford, for his column on ‘Hornblower in Space’

BooksReadingOrder, for your quick, easy references to publication dates

Honorverse fandom, for gaps in my own in-universe knowledge

David Weber and TOR.com, for his own thoughts on the writing process

David Mattingly, for all his artwork across the series